Pemphigus symptoms

The characteristic symptoms of pemphigus are a rash of small blisters with serous contents. Their localization depends on what form of the disease develops:

- ordinary - rashes appear on the mucous membrane, accompanied by an unpleasant odor;

- leafy – blisters form on the skin, and crusts form at the same time;

- non-acantholytic - rashes are located on the mucous membrane and lips. This form of pathology is more often diagnosed in old age.

With pemphigus in children and adults, the following are also observed:

- severe weakness;

- increased drowsiness;

- deterioration or complete loss of appetite;

- losing weight even while eating high-calorie foods.

To detect pemphigus in newborns, older children and adults, the following examination methods are used:

- examination of the patient and assessment of rashes;

- Nikolsky test - with its help, differential diagnosis with other skin diseases is carried out;

- histological and cytological examination.

The symptoms of pemphigus (the second name of the disease) are often similar to the symptoms of other pathologies that will require completely different therapy. Therefore, before prescribing treatment, a thorough study of the symptoms that have arisen will be required.

Home > Therapeutic

dentistry

> Diseases of the oral mucosa > Lesions of the oral mucosa with dermatoses > Pemphigus Pemphigus

Pemphigus (true, acantholytic) is a severe dermatovirus or autoimmune origin, characterized by the formation of blisters and erosions on the oral mucosa and skin. This disease mainly affects people over 35 years of age.

There are 4 clinical forms of pemphigus: vulgar, vegetative, foliaceous and seborrheic. Often the process begins in the oral cavity, then spreads to the skin and other mucous membranes, so the dentist can be the first to identify this disease and take emergency measures to treat it.

Changes in the oral mucosa with pemphigus for a long time (several months or even years) may be the only symptoms of the disease. In the mouth, the cheeks, palate, floor of the mouth, lips, and pharynx are most often affected.

In the oral cavity, the process proceeds somewhat differently than on the skin, which can be explained by the structural features of the mucous membrane. Typical bubbles are usually not observed here. Initially, the mucous membrane at the site of the lesion becomes cloudy, erosion occurs in the center of the lesion, quickly spreading to the periphery. Characteristic of pemphigus is Nikolsky’s symptom - if you pull the mucous membrane along the edge of the erosion, it will peel off on apparently healthy tissues. The pain from erosions is quite severe, especially when eating and talking. If there are damaged and untreated teeth, tartar and plaque in the oral cavity, then pyogenic microflora can join the rashes, which significantly complicates the process. A strong putrid odor appears, and the general condition deteriorates sharply.

In addition to the mucous membrane of the oral cavity and skin, pemphigus can also affect other mucous membranes: the pharynx, esophagus, stomach, and intestines. Lesions of internal organs are often found in pemphigus, as well as significant changes in the central and peripheral nervous system.

Pemphigus usually occurs chronically, less often acutely. Before the use of modern treatment methods, the duration of the disease was from 2 months to 2 years, and the outcome was usually fatal.

Treatment is carried out jointly by dermatologists and dentists.

Local treatment is aimed at fighting the associated infection, deodorizing the oral cavity, and reducing pain. Thorough sanitation of the oral cavity, antiseptic solutions in low concentrations, and painkillers in the form of baths, applications, and lubricants are recommended. When the lips are affected, antibiotic ointments, an oil solution of vitamin A, etc., ease the suffering of patients.

Pemphigus of the mouth and extremities: Topic overview

What is viral pemphigus of the mouth and extremities in children?

Viral pemphigus of the mouth and extremities in children is a common childhood disease. The disease causes swelling in the mouth, hands, feet, and sometimes on the buttocks and legs. A swelling in the mouth can cause a lot of pain and may make it difficult for your child to eat. This is not a dangerous condition and all symptoms usually go away after a week or so.

The disease occurs at any time of the year, but most often viral pemphigus of the mouth and extremities occurs in summer and autumn.

Viral pemphigus of the mouth and extremities has nothing in common with other diseases that have similar names: foot and mouth disease (sometimes this disease is also called thrush) or “ mad cow disease ”. These diseases occur almost exclusively in animals.

What causes viral pemphigus of the mouth and extremities in children?

Viral pemphigus of the mouth and extremities in children is a common childhood disease caused by a virus called enterovirus (intestinal virus).

The virus spreads easily through sneezing and coughing. You can also become infected by coming into contact with contaminated stool, such as when changing diapers. Very often, disease outbreaks occur within community boundaries. Most often, children spread the disease during the first few weeks of illness. But the virus persists in stool and can sometimes spread for several months after the blisters have subsided and the wounds have healed.

It usually takes 3 to 6 days after a person exposed to oral and extremity pemphigus virus develops symptoms. This is called the incubation period.

What are the symptoms?

At first, the child may feel tired, have a sore throat, and a fever. Then, after a day or two, the child may develop sores or blisters on the hands, feet, mouth, and sometimes on the thighs. In some cases, the child will develop a rash before the blisters appear. The blisters may burst and crust over. The wounds and blisters disappear in about a week.

How is viral pemphigus of the mouth and extremities diagnosed in children?

The doctor will be able to make a diagnosis of viral pemphigus of the mouth and extremities based on the manifestation of the symptoms described above and based on examination of the wounds and blisters.

How to treat this disease?

Viral pemphigus of the mouth and extremities in children does not require special treatment. In most cases, the disease goes away within 7-10 days. You can use the following tips to ease your child's symptoms:

- Encourage your child to drink plenty of cool drinks. You can also offer your child carbonated drinks and ice cream.

- Avoid giving your child sour or hot or spicy foods and drinks, such as salsa or orange juice. These foods can irritate the tissues in your mouth.

- To relieve pain or reduce fever, give your child acetaminophen (such as Tylenol) or ibuprofen (such as Advil). Do not give your child aspirin, as it has been linked to Reye's syndrome.

To prevent the disease from spreading:

- Encourage all family members to wash their hands frequently. It is very important to wash your hands after changing the diapers of a sick child. This happens because the virus can persist in stool for months on end after the blisters have gone away.

- Do not allow your child to share toys or kiss him while he is infected.

- If your child goes to school or daycare, talk to staff about when your child can return.

- Wear latex or rubber gloves when applying lotion, cream, or ointment to your child's blisters.

| foot and mouth disease Foot and mouth disease is a viral infection that occurs in animals, such as cattle, sheep, and pigs (even-toed ungulates). This disease is in no way related to viral pemphigus of the mouth and extremities, which occurs in humans - the two diseases are caused by completely different viruses. The foot-and-mouth disease virus can spread from animal to animal through direct contact with an infected animal or through contact with food or other objects that have been contaminated. Animal caregivers can spread the disease from one animal to another through contaminated clothing, shoes, or other contaminated items. Mad cow disease Mad cow disease (bovine spongiform encephalopathy, BSE) is a degenerative and usually fatal disease that affects the central nervous system of cattle, sheep, and goats. People cannot get mad cow disease, but in very rare cases they get a form of the disease called Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease if they eat nerve tissue (brain or spinal cord) from cattle infected with mad cow disease. No one knows for sure what causes mad cow disease. According to one theory, the disease is caused by a change in the shape of certain proteins that are found in animal cells. Similar changes can be caused by other abnormal proteins called prions. In infected cows, abnormal proteins (prions) are found in the brain, spinal cord, and small intestine. Another theory is that mad cow disease is caused by a virus that causes proteins to change to abnormal levels (prions). Enterovirus Enteroviruses, such as Coxsackievirus and ECHO viruses, live in the intestines of people and other animals. Enteroviruses usually do not cause disease, but under certain conditions they can. Infected people pass viruses from each other through contaminated food, water, or other objects. |

Publications in the media

True pemphigus is accompanied by the appearance of blisters on unchanged skin or mucous membranes, which tend to generalize and merge. Frequency. Up to 1% of all skin diseases. It occurs at any age, but people aged 40 to 60 years are more likely to suffer, women more often than men.

Pathogenesis. In some cases, the formation of autoantibodies to keratinocyte glycoproteins—desmogleins 1 and 3 (125670, *125671, 169615, DSG1, DSG3, 18q12 genes) that are part of desmosomes—has been recorded. These glycoproteins are known as Ag PVA of pemphigus vulgaris and pemphigus foliaceus. Autoantibodies to PVA recognize the cell surface glycoprotein of keratinocytes, which leads to loss of intercellular adhesion. Pathohistology . Characterized by intercellular edema, destruction of desmosomes in the suprabasal layers of the epidermis, and the formation of blisters. In the cavity of the bladder, single and groups of round-shaped acantholytic cells with large vesicular nuclei and pale cytoplasm are visible. With direct immunofluorescence microscopy: a clear glow of IgG and C3 complement components in the intercellular spaces of the epidermis. In pemphigus vegetans there is pronounced acanthosis, papillomatosis and intraepidermal microabscesses of eosinophils. In pemphigus foliaceus, acantholysis occurs in the upper layers of the epidermis—granular and subcutaneous.

Clinical picture and classification • Vulgar (ordinary) pemphigus. On normal skin or mucous membranes, single blisters appear, sometimes reaching the size of a walnut, with transparent, gradually becoming cloudy, rarely hemorrhagic contents. Some blisters collapse and their contents shrink into crusts, others rupture and form erosions. Nikolsky's symptom is positive. Acantholytic cells are found in fingerprint preparations from the bottom of the erosion. • Seborrheic (erythematous) pemphigus of Senir-Ascher. The process often begins on the face, back, chest or scalp. The primary element is a bubble of small size (unlike the bubble of pemphigus vulgaris), which quickly dries into grayish-yellowish crusts, upon removal of which an erosive surface is revealed. Nikolsky's symptom is positive. Acantholytic cells are not always found. • Pemphigus foliaceus (exfoliative). Rarely registered. The blisters are flaccid, and erythematous-squamous large-lamellar dermatosis gradually develops. Nikolsky's symptom is sharply positive. • Pemphigus vegetans (Neumann's disease). Rarely registered. The initial lesions are localized on the mucous membrane of the oral cavity and on the skin of the corners of the mouth, on the lips, in the axillary and inguinal-femoral folds, on the genitals, around the navel and anus, in women - under the mammary glands. First, quickly bursting blisters appear, at the bottom of which gradually enlarging, sometimes bleeding, vegetations form. Nikolsky's symptom is positive. Acantholytic cells are always found. Diagnosis is based on a combination of the results of clinical, cytological, histological and immunological examinations. In all forms of pemphigus, IgG deposition is noted in the intercellular adhesive substance of the epidermis. Histologically, horizontal cracks and cavities above the basement membrane and acantholytic cells are revealed.

Differential diagnosis • Eczema • Dermatomycosis • Herpes • Herpes zoster • Exudative erythema multiforme • Bullous impetigo • Pemphigoid • Dermatitis herpetiformis. Treatment • GC - prednisolone systemically 70-150 mg/day and topically (betamethasone) • Immunosuppressants - methotrexate, cyclosporine • To prevent electrolyte imbalance - potassium, calcium preparations • To prevent the catabolic effect of GC - anabolic hormones. Complications associated with long-term use of GCs • Itsenko-Cushing syndrome • Formation of ulcers in the gastrointestinal tract • Diabetes • Arterial hypertension • Psychosis • Exacerbation of foci of chronic infection • Osteoporosis. Current and prognosis . The disease lasts a long time, for years, with remissions and relapses. Pemphigus vulgaris sometimes has an acute malignant course and, despite treatment, ends in death after a few months. Prevention. Long-term maintenance therapy with GCs, regular monitoring of blood and urine glucose levels, prothrombin, and blood pressure. Assessment of working capacity, if necessary, registration of disability group III or II. It is recommended to adhere to a work-rest regime; significant physical activity and increased insolation should be avoided. Following a diet high in proteins and vitamins. Eating large quantities of food is not recommended. Limit the consumption of table salt, carbohydrates and fats. Synonyms • Pemphigus • Acantholytic pemphigus • Pemphigus vulgaris

ICD-10 • L10 Pemphigus [pemphigus]

Pemphigus

Pemphigus has a long, undulating course, and the lack of adequate treatment leads to disruption of the patient’s general condition. In the vulgar form

pemphigus blisters are localized throughout the body, have different sizes and are filled with serous contents, while the covering on the blisters is sluggish and thin.

Pemphigus vulgaris usually makes its debut on the mucous membranes of the mouth and nose, and therefore patients receive therapy from dentists and otolaryngologists for a long time and without success. At this stage of pemphigus, patients complain of pain during eating and talking, hypersalivation and a specific bad breath. The duration of this period is from three months to a year, after which pemphigus becomes widespread and the skin is involved in the inflammatory process.

Sometimes patients do not notice the presence of blisters because of their small size and thin covering; the blisters open quickly, and therefore the main complaints of patients with pemphigus at this period are painful erosions. Long-term and unsuccessful therapy for stomatitis is carried out before pemphigus is diagnosed. Blisters that are localized on the skin tend to spontaneously open, exposing the eroded surface and the remains of the tire, which shrinks into crusts.

Erosion in pemphigus is bright pink, with a smooth glossy surface; they differ from erosion in other diseases by their tendency to grow peripherally and to generalize with the formation of extensive lesions. If pemphigus takes this course, the patient’s general condition worsens, intoxication develops, a secondary infection develops, and without proper treatment, such patients die. With pemphigus vulgaris, Nikolsky syndrome is positive in the lesion and sometimes on healthy skin - with minor mechanical impact, detachment of the upper layer of the epithelium occurs.

Erythematous pemphigus

differs from vulgar in that at the beginning the skin is affected; erythematous lesions on the chest, neck, face and scalp are seborrheic in nature, have clear boundaries, the surface is covered with yellowish or brown crusts of varying thickness. If these crusts are separated, the eroded surface is exposed.

With erythematous pemphigus, the blisters can be small, their cover is flabby and sluggish, they spontaneously open very quickly, therefore it is extremely difficult to diagnose pemphigus. Nikolsky's symptom, as with erythematous pemphigus, can be localized for several years, then, as the process generalizes, it acquires vulgar features. Erythematous pemphigus should be differentiated from lupus erythematosus and seborrheic dermatitis.

Pemphigus foliaceus

clinically manifested by erythematous-squamous rashes, thin-walled blisters tend to appear on previously affected areas; after opening the blisters, a bright red eroded surface is exposed, upon drying of which lamellar crusts are formed. Since with this form of pemphigus blisters also appear on the crusts, the affected skin is sometimes covered with a massive layered crust due to the constant separation of exudate. Pemphigus leaf affects the skin, but in very rare cases, lesions of the mucous membranes are observed; it quickly spreads throughout healthy skin and at the same time there are blisters, crusts and erosions on the skin, which merge with each other to form an extensive wound surface. Nikolsky's symptom is positive even on healthy skin; with the addition of pathogenic microflora, sepsis develops, which usually causes the death of the patient.

Pemphigus vegetans

It is more benign, sometimes patients remain in satisfactory condition for many years. The blisters are localized around natural openings and in the area of skin folds. Opening up, the bubbles reveal erosions, at the bottom of which soft vegetations with a fetid odor are formed; the vegetations are covered on top with a serous or serous-purulent coating. There are pustules along the periphery of the formations, and therefore vegetative pemphigus must be differentiated from vegetative chronic pyoderma. Nikolsky syndrome is positive only near the affected skin, but in the terminal stages pemphigus vegetans is similar to pemphigus vulgaris in its clinical manifestations.

Clinical case of pemphigus vulgaris in old age

True pemphigus is one of the most serious diseases. It accounts for 0.7 to 1% of all skin diseases [1, 4]. According to the regional dermatovenerological dispensary in Astrakhan for 2014, only 9 patients with pemphigus were treated as inpatients. Pemphigus can occur at any age. Most often, women over 40 years of age are affected; in recent years, cases of the disease among young people aged 18 to 25 have become more frequent. The most severe course is observed between the ages of 30 and 45 years [1, 4]. Pemphigus (acantholytic, or true, pemphigus) is an autoimmune disease characterized by the appearance of intraepidermal blisters on apparently unchanged skin and/or mucous membranes. The characteristic morphological basis is suprabasal blisters with acantholysis [4, 7, 8]. The etiology of pemphigus still remains unknown [1]. Currently, the leading role of autoimmune processes that develop in response to changes in the antigenic structure of epidermal cells under the influence of various damaging agents is recognized. Cell damage is possible as a result of chemical, physical, and biological factors [4]. It was found that in pemphigus, autoantibodies are directed against the surface structures of epidermal cells - keratinocytes. The binding of autoantibodies (pemphigus IgG) to glycoproteins of cell membranes (pemphigus antigens) of keratinocytes leads to acantholysis - impaired adhesion between cells and the formation of blisters. It has been shown that the complement system and inflammatory cells are not involved in this process, although the presence of complement enhances the pathogenicity of autoantibodies, and infection in areas of skin damage leads to the addition of an inflammatory process, which aggravates the patient’s condition [6]. Risk factors for the development of true pemphigus may include various exogenous and endogenous factors (including genetic predisposition). HLA-DR and HLA-DQ polymorphisms have been shown to be the basis of genetic predisposition to pemphigus (and other autoimmune diseases) [4, 6].

There are four clinical forms of true pemphigus: vulgar (ordinary), vegetative, foliate and erythematous (seborrheic). All clinical varieties are characterized by a long-term chronic wave-like course, leading in the absence of treatment to a disturbance in the general condition of the patients. Pemphigus vulgaris is the most common (up to 80% of all cases) [4]. In more than 50% of cases, the disease begins with damage to the mucous membranes of the oral cavity and pharynx. Small flabby blisters with serous contents that appear on unchanged mucous membranes, initially single or few in number, can be located in any area. Over time, their number increases. The blisters quickly (within 1–2 days) open, forming weeping, painful erosions with a bright red bottom or erosions covered with a whitish coating, bordered along the periphery by fragments of whitish epithelium. With further intensification of the erosion process, they become numerous, increase in size and, merging with each other, form foci of scalloped outlines. Patients experience pain when eating, talking, or swallowing saliva. A characteristic symptom is hypersalivation and a specific putrid odor from the mouth. If the larynx and pharynx are affected, the voice may be hoarse. For a long time, patients are observed by dentists or ENT doctors for stomatitis, gingivitis, rhinitis, laryngitis, etc. Damage to the mucous membranes can remain isolated from several days to 3–6 months. and more, and then the skin of the torso, limbs, and scalp is involved in the process.

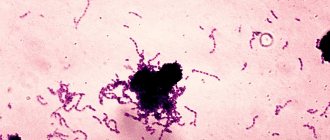

Skin damage begins with the appearance of single blisters, then their number increases. The blisters are located on an unchanged, less often on an erythematous background. They are small in size, have a tense tire and serous contents. After a few days, some blisters on the skin dry out into yellowish crusts, or when the tire ruptures, bright red erosions may be exposed, releasing a thick exudate. Erosions at this stage of the disease are not painful and quickly epithelialize. The general condition of the patients remains satisfactory. The rashes that have regressed are replaced by new ones. This initial phase can last from 2-3 weeks. up to several months or even years. Then comes the generalization of the process, characterized by the rapid spread of rashes over the skin and the transition to the mucous membranes of the oral cavity and genitals, if they were not previously affected. As a result of eccentric growth due to exfoliation of the upper layers of the epidermis, the blisters increase in size, the tire becomes flabby, and the contents become cloudy or purulent. Under the weight of exudate, large blisters can take on a pear-shaped form (“Sheklakov’s pear syndrome”). The blisters spontaneously burst with the formation of extensive eroded areas of the skin. Erosions in pemphigus vulgaris are usually bright pink in color with a shiny, moist surface. The peculiarity of erosions is a tendency to peripheral growth, while generalization of the skin process with the formation of extensive lesions, deterioration of the general condition, the addition of a secondary infection, the development of intoxication and, in the absence of treatment, death are possible [1–5]. An important diagnostic sign of pemphigus vulgaris is Nikolsky’s symptom: detachment of the apparently unchanged epidermis when pressing on its surface near the bubble or even on apparently healthy skin far from the lesion [1]. There are three variants of Nikolsky's symptom, which allow us to assess the prevalence of acantholysis. In the first case, when the tire of a burst bladder is pulled, the epidermis peels off beyond its borders. In the second option, the upper layer of the epidermis peels off, and an erosive surface is formed if healthy skin is rubbed between two blisters. The appearance of erosion after rubbing healthy skin in a place near which there are no bullous elements indicates the presence of the third variant of Nikolsky’s symptom [5]. A modification of Nikolsky's symptom is the Asbo-Hansen phenomenon: finger pressure on the tire of an unopened bladder increases its area due to further stratification of the acantholytically altered epidermis with vesical fluid. In the initial phase of pemphigus vulgaris, Nikolsky’s symptom is not always detected, and even then only in the form of a marginal one. When the process is generalized, it is positive in all patients in all modifications [3]. Diagnosis of true pemphigus is based on the totality of the results of clinical, cytological, histological and immunological examination. The clinical picture of the disease, the presence of a positive Nikolsky symptom and its modification, the “pear” phenomenon described by N.D. are taken into account. Sheklakov, which are based on the phenomenon of acantholysis. Cytological examination reveals acantholytic cells (Tzanck cells) in impression smears from erosions and blisters after staining using the Romanowsky-Giemsa method (Tzanck test). The presence of Tzanck cells in the blisters is not pathognomonic, but a very important diagnostic sign of the disease.

Histological examination reveals the intraepidermal location of cracks and blisters [1, 4]. A necessary condition for a qualified diagnosis of true pemphigus is an immunofluorescence study. By means of indirect immunofluorescence, antibodies against components of the epidermis are detected when treated with luminescent anti-IgG human serum. Using direct immunofluorescence, IgG antibodies are detected in skin sections, localized in the intercellular spaces of the spinous layer of the epidermis [1]. Laboratory data (anemia, leukocytosis, increased ESR, proteinuria, hypoalbuminemia, decreased sodium excretion in urine, etc.) play a certain supporting role, allowing one to assess the severity of the process [3]. Differential diagnosis is carried out with Lever's bullous pemphigoid, Dühring's dermatitis herpetiformis, chronic benign familial pemphigus Gougereau-Hailey-Hailey, lupus erythematosus, seborrheic dermatitis, Lyell's syndrome, chronic pyoderma vegetans [4].

Treatment of true pemphigus has so far caused great difficulties. Since the main links of pathogenesis are interpreted from the standpoint of autoimmune pathology, all existing therapeutic measures are reduced to immunosuppressive effects on autoallergic processes through the use of corticosteroid and cytostatic drugs [1]. The introduction of corticosteroids into the treatment of pemphigus reduced mortality among patients from 90 to 10% [6]. Pemphigus is one of the few diseases in which corticosteroids are prescribed for health reasons, and existing contraindications in these cases become relative. The positive effect of glucocorticoids is explained primarily by the blockade of key stages of the biosynthesis of nucleic acids and proteins, shutdown of the afferent phase of immunogenesis, reduction of lymphoid organs, destruction of medium and small thymic lymphocytes, and inhibition of the formation of immune complexes. It is also believed that corticosteroids have a stabilizing effect on lysosome membranes and inhibit the synthesis of autoantibodies [1]. Typically, pemphigus vulgaris and pemphigus foliaceus are the most severe, therefore, for these clinical forms, the highest doses of glucocorticosteroids are prescribed (from 60–100 to 150–300 mg/day of prednisolone equivalent) [1,4]. The dose of prednisolone is selected taking into account the prevalence of the rash and the severity of the disease. It should be at least 1 mg/kg/day. The daily dose is distributed in such a way that 2/3 falls in the early morning hours (preferably after meals), and 1/3 in the afternoon (12–13 hours). If the patient’s condition is particularly severe, higher doses of prednisolone are prescribed – up to 300 mg/day [4]. At high doses, prednisolone can be partially replaced by parenteral administration or betamethasone (it is possible to use prolonged forms once every 7-10 days). Long-term use of corticosteroid drugs leads to the development of serious complications and side effects, and if they are quickly discontinued, the so-called withdrawal syndrome occurs, and the disease recurs. Therefore, it is necessary to correct and prevent side effects caused by long-term use of glucocorticosteroids. In order to prevent withdrawal syndrome, it is recommended to stop taking medications or reduce their daily dose carefully and gradually. Initially, a reduction in the dose of glucocorticosteroids is possible by 1/4–1/3 of the maximum initial dose after achieving a clear therapeutic effect (cessation of the appearance of new blisters, active epithelization of erosions), which usually occurs after 2–3, sometimes after 4 weeks. Then the dose of prednisolone is gradually, slowly, over several months, reduced to maintenance. The daily dose of the hormone is gradually reduced, approximately once every 4–5 days by 2.5–5 mg of prednisolone until the minimum maintenance effective dose of the corticosteroid is reached, the administration of which ensures remission of the disease.

In the future, a maintenance dose of corticosteroids is recommended to be administered alternately. However, periodically (every 4–6 months) it should be reduced by 2.5 mg prednisolone equivalent. Thus, by reducing the maintenance dose, it is possible to reduce the amount of hormone administered by 3-4 times compared to the initial maintenance dose. The maximum permissible minimum maintenance dose can vary from 2.5 to 30 mg/day. Typically, patients with pemphigus receive glucocorticosteroids for life, and sometimes their use can be abandoned [1, 4]. The addition of second-line drugs to therapy is indicated to increase the effect of treatment, reduce the side effects of corticosteroids, and also to prevent relapses during their gradual withdrawal. Adjuvant therapy includes azathioprine, methotrexate, cyclophosphamide, mycophenolate mofetil, intravenous immunoglobulin and dapsone [8]. The combined use of cytostatic and immunosuppressive drugs with corticosteroids allows one to achieve good therapeutic results in a shorter time and with lower daily doses of corticosteroids. Many drugs, such as alkylating agents and antimetabolites, have cytostatic properties. Of the alkylating agents, cyclophosphamide is the most widely used in the treatment of pemphigus. This drug is capable of entering into alkylation reactions with certain groups of proteins and nucleic acids of the cell, inhibiting various enzyme systems and dramatically disrupting the vital activity of cells, primarily highly active and lymphoid ones. Antimetabolites, which include purine base antagonists (azathioprine) and folic acid antagonists (methotrexate), resemble the structure of natural cell metabolites and, by competing with them, disrupt intracellular metabolism. The consequence of this is the accumulation of substances toxic to cells, leading to the death of cells, primarily actively proliferating ones. Azathioprine is prescribed at a dose of 1.5–2 mg/kg/day in 2–4 divided doses in combination with steroids. Methotrexate is administered intramuscularly at 10–20 mg (with good tolerance up to 25–30 mg) 1 time per week (for a course of 3–5–8 injections). Cyclophosphamide is administered orally at 100–200 mg/day, the duration of therapy is determined individually. During treatment, monitoring of blood tests (general and biochemical) and urine is necessary.

If the therapeutic effectiveness of glucocorticosteroids is insufficient and there are contraindications to the use of cytostatics, immunosuppressants are prescribed. Cyclosporine A for the treatment of patients with true pemphigus is used in combination with corticosteroid drugs, and the daily dose of corticosteroids is reduced by 3-4 times and corresponds to 25-50 mg of prednisolone equivalent. The daily dose of cyclosporine A in the complex therapy of patients with true pemphigus in the acute stage should not exceed 5 mg per 1 kg of the patient’s body weight and averages 3–5 mg/kg/day. This takes into account the clinical picture, severity and prevalence of the disease, the patient’s age, and the presence of concomitant diseases. For the first 2 days, to assess the tolerability of the drug, cyclosporine A is prescribed in half the dose, subsequently the daily dose is divided into 2 doses - morning and evening with an interval of 12 hours. The daily dose of cyclosporine A begins to be reduced after intensive epithelization of existing erosions. Typically, a loading dose is taken on average for 14–20 days, followed by a gradual reduction in the daily dose of the drug to 2–2.5 mg per 1 kg of the patient’s body weight. Complete cleansing of the skin should not be considered the final goal of treatment. After achieving remission, the patient should continue to take the minimum effective maintenance dose of cyclosporine A, which should be selected individually. At this dosage, the drug can be used for a long time (2–4 months) as maintenance therapy. Currently, treatment with immunosuppressants is not generally accepted [1, 4]. Aniline dyes, corticosteroid creams with an antibacterial or antimycotic component, and aerosols are used locally [3]. For additional treatment of pemphigus, extracorporeal detoxification methods (hemosorption, plasmapheresis) are successfully used [1]. Despite the successes of domestic and foreign researchers in clarifying the mechanisms of pathogenesis and improving treatment methods for patients with true pemphigus, the problem of pemphigus remains relevant and is due to the severity of the disease, its incurability and potential mortality [1].

We present a clinical case demonstrating the difficulties of differential diagnostic search when diagnosing pemphigus. Patient Zh., born in 1945, has been ill since the fall of 2014, when rashes first appeared on the scalp. I treated myself, used ointments with antibiotics without effect. In May 2015, an exacerbation of the skin process began. The rash has spread to the face and torso. He was observed in the clinic at his place of residence, and due to the torpidity of treatment, he was sent to the regional oncology clinic, where a pathohistological examination of the scalp was carried out. After examination, a diagnosis was made: multiple scalp cancer. Т1N0М0. Radiation therapy is recommended. Within 2 weeks. the process on the skin has spread significantly: elements have appeared on the chest, back, and upper limbs. Serous-purulent discharge was noted on the scalp, and the erosions took on a draining character. Taking into account the change in the clinical picture, he was sent for consultation to the regional dermatovenerological clinic with a diagnosis of pemphigus vulgaris. As a result of examination in the department, this diagnosis was clinically and laboratory confirmed. At the same time, pathohistological preparations were reviewed at the oncology clinic, and the diagnoses of cancer and basal cell carcinoma of the scalp were removed as erroneous. From the anamnesis it is known that the patient has a burdened premorbid background. In 2012, he suffered a small-focal myocardial infarction. Suffering from chronic bronchitis. Upon examination, a widespread pathological process was revealed. On the skin of the scalp, face, neck, torso and upper extremities there were multiple bright red erosions with serous and serous-purulent discharge. Some of the erosions were covered with dense crusts of gray-yellow color (Fig. 1–3). On an erythematous background, there were blisters of various sizes with a flabby cap and cloudy contents. Nikolsky's symptom is positive. During a laboratory examination, smears from blisters on the forearms revealed single acantholytic cells in a specimen with coarse nuclei. Epithelial cells with signs of atypia (enlarged coarse nuclei, binucleate cells) up to 8–10–12 per field of view were identified. During bacteriological examination of discharge from erosions, staphylococcus was isolated. According to the pathomorphological study, the morphological picture of pemphigus was revealed - a bubble with serous fluid and acantholytic cysts with purulent inflammation along the periphery was found in the epidermis. When reviewing the drugs at the oncology center, the morphological picture of pemphigus was confirmed and no tumor growth was detected. A general clinical examination showed an increase in ESR and a sharply positive C-reactive protein. Fibrogastroduodenoscopy revealed erosive antrum gastritis, erosive and ulcerative bulbitis and duodenitis. Small (up to 0.2 cm) acute ulcers of the bulb and the upper horizontal part of the bulb were found.

Taking into account the generalized process of skin lesions, parenteral administration of prednisolone at a dose of 90 mg was prescribed with a gradual transition to oral administration of the drug at a dose of 30 mg. He also received detoxification, antibacterial and antifungal systemic therapy and local treatment using antiseptics, reparatives and anti-inflammatory drugs. Due to the presence of erosive gastritis, erosive-ulcerative bulbitis, and also because of taking prednisolone, the patient was given antisecretory therapy. During therapy for 3 weeks. positive dynamics were noted. On the skin of the scalp, neck, chest, and back, erosions were completely epithelialized, and the crusts fell off (Fig. 4–6). He was discharged for outpatient treatment with recommendations to reduce the dose of prednisolone by 1/4 tablet every 7–10 days under the supervision of a dermatovenerologist at the place of residence.

The development of pemphigus in a 70-year-old man with a latent onset of the disease may have been the reason for late diagnosis and, consequently, untimely initiation of therapy. After correct interpretation of clinical and morphological data and complex therapy, a positive result was achieved.

Literature 1. Matushevskaya E.V. Pemphigus // Russian Medical Journal. 1997. No. 11. 2. Mordovtsev V.N., Mordovtseva V.V., Alchangyan L.V. Erosive and ulcerative skin lesions // Consilium Medicum. 2000. No. 5. 3. Paltsev M.A., Potekaev N.N., Kazantseva I.A., Kryazheva S.S. Clinical and morphological diagnosis and principles of treatment of skin diseases. Guide for doctors. M.: Medicine, 2010. 4. Kubanova A.A., Kisina V.I., Blatun L.A., Vavilov A.M. and others. Rational pharmacotherapy of skin diseases and sexually transmitted infections: A guide for practitioners / edited by. ed. A.A. Kubanova, V.I. Kisina. M.: Litterra, 2005. 882 p. (Rational pharmacotherapy: ser. handbook for practicing physicians; vol. 8). 5. Rubins A. Dermatovenerology. Illustrated guide. M.: Panfilov Publishing House, 2011. 368 p. 6. Svirshchevskaya E.V., Matushevskaya E.V. Immunopathogenesis and treatment of pemphigus // Russian Medical Journal. 1998. No. 6. 7. Kumar R., Jindal A., Kaur A., Gupta S. Therapeutic Plasma Exchange-A New Dawn in the Treatment of Pemphigus Vulgaris // Ind. J. Dermatol. 2015. Vol. 60(4). P. 419. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.160509. 8. Quaresma MV, Bernardes-Filho F., Hezel J. et al. Dapsone in the treatment of pemphigus vulgaris: adverse effects and its importance as a corticosteroid sparing agent // An. Bras. Dermatol. 2015. Vol. 90 (3 Suppl. 1). R. 51–54.